Welcome.

This is where I share pages from my notebooks as I travel far and and near to discover places and spaces and nature’s architecture.

I hope you enjoy the journey.

Welcome.

This is where I share pages from my notebooks as I travel far and and near to discover places and spaces and nature’s architecture.

I hope you enjoy the journey.

I nearly missed Antarctica. I was looking for something specific, something silent and empty, the ultimate study in white space. It showed up in the nick of time, just not where I’d been looking for it….

Read the essay in

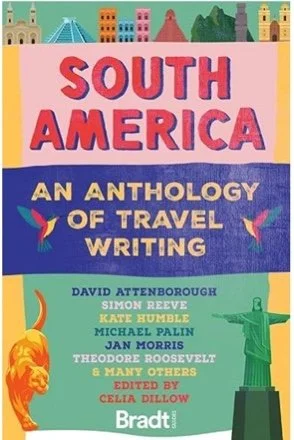

South America: An Anthology of Travel Writing

Published 25th July 2025 by Bradt Guides

The world’s leading independent travel publisher

Available at

BradtGuides.com

Stanfords.co.uk

Amazon.com

and wherever books are sold.